Child Hates School | What to Do When Your Child Says ‘I Hate School’ — Scripts and Actions for Different Ages

A research-backed guide to understanding why children refuse school and how to help them through anxiety, boredom, bullying, learning challenges, and burnout

It’s Monday morning. Your eight-year-old is sitting on the stairs, tears streaming down their face, refusing to put on their shoes.

“I hate school,” they say. “I’m not going.”

Your heart sinks. This is the third time this month. You feel torn between empathy for your child’s distress and the pressure to get them through the school doors. You wonder if you’re being too soft or not supportive enough. Is this normal childhood resistance, or something more serious?

You’re not alone. According to the National Institutes of Health, as many as 28% of children experience school avoidance at some point, with the highest rates occurring among children ages 10–13 and during school transitions.1

But here’s what most parents don’t realize: “I hate school” is rarely about hating school itself.

This single phrase can mean vastly different things depending on what’s happening beneath the surface. A child experiencing anxiety sounds remarkably similar to one who’s bored, being bullied, struggling with undiagnosed learning difficulties, or simply burned out from academic pressure.

Practical Parenting Tips That Work

If school stress is just one part of what you’re juggling, these simple real-parenting tips help strengthen connection, reduce overwhelm, and build resilience at home.

→ Read 5 Real Parenting Tips That Actually HelpThis guide will help you identify what’s really going on, provide you with age-appropriate language to use with your child, and give you a clear action plan based on current pediatric and psychological research.

Quick Answers for Parents in a Hurry

Yes, occasional school resistance is developmentally normal. Most children express reluctance about school at some point. However, when it becomes frequent (more than once per week), is accompanied by physical symptoms, or significantly impacts daily functioning, it warrants closer attention.

Be concerned if your child shows persistent physical complaints only on school days, experiences panic or meltdowns before school, has declining academic performance, withdraws socially, or if avoidance continues for more than two weeks despite your supportive efforts.

Anxious children show physical symptoms (stomachaches, nausea, tears), fear specific situations, and feel relief when allowed to stay home. Bored children are physically fine, complain that school is “pointless” or “easy,” and may be more engaged in non-school activities during the day.

Start with validation: “I hear that you’re having a hard time with school right now.” Then move to curiosity: “Can you help me understand what’s the toughest part about going?” Avoid dismissing their feelings or jumping immediately to solutions.

Why Children Say “I Hate School”

Children, particularly younger ones, don’t have the vocabulary or emotional sophistication to articulate complex feelings. “I hate school” becomes emotional shorthand for a wide range of experiences:

- Overwhelm — “There’s too much happening and I can’t process it all”

- Fear — “Something there makes me feel unsafe”

- Inadequacy — “I can’t keep up and I feel like I’m failing”

- Social pain — “I don’t have friends” or “Kids are mean to me”

- Understimulation — “Nothing challenges me and I’m wasting time”

- Exhaustion — “I’m too tired to cope with the demands”

According to research published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, school refusal is not a diagnosis itself but rather a symptom associated with various underlying conditions, including anxiety disorders (most common), depression, oppositional defiant disorder, specific phobias, and adjustment disorders.2

The Developmental Context

Children’s brains are still developing executive function skills — the mental processes that help us plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks. The prefrontal cortex, which manages these skills, isn’t fully developed until the mid-20s.

This means that:

- Young children may struggle to identify why they don’t want to go to school

- They may attribute feelings to the wrong source (blaming “school” when they’re actually anxious about a specific peer interaction)

- Their emotional responses can be intense and seem disproportionate to adults

- They may communicate distress through behavior rather than words

Understanding this developmental context helps parents approach the situation with appropriate expectations and patience.

Help Your Child Understand Their Feelings

Emotional intelligence makes a huge difference when kids feel overwhelmed by school. Learn how to nurture emotional awareness and effective self-expression at home.

→ Explore How to Raise Emotionally Intelligent Kids at HomeDifferentiating the Cause: What’s Really Going On?

The key to helping your child is accurately identifying the root cause. Here’s a comprehensive comparison of the five most common underlying issues:

| Indicator | Boredom | Anxiety | Bullying | Learning Difficulty | Burnout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Signs | No physical symptoms; complains work is too easy; finishes early; disengaged in class | Physical complaints (headache, stomachache); clinginess; tearfulness; panic before school; relief when staying home | Physical injuries; missing belongings; fear of specific locations or times; sudden social withdrawal; nightmares | Avoidance of homework; frustration during reading/math; drop in grades; “I’m stupid” statements; takes much longer than peers | Chronic fatigue despite sleep; emotional flatness; loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities; irritability; perfectionism |

| What Child Says | “School is pointless”; “I already know this”; “It’s so boring”; “When will we learn something new?” | “My stomach hurts”; “What if I throw up?”; “I miss you”; “Something bad will happen”; “I can’t do this” | “Kids are mean”; “I have no friends”; “Everyone hates me”; may be reluctant to provide details; or goes silent | “I can’t do it”; “It’s too hard”; “I’m dumb”; “Everyone else gets it but me”; avoids mentioning specific subjects | “I’m so tired”; “I can’t anymore”; “What’s the point?”; “Nothing I do is good enough” |

| Common Parent Mistake | Dismissing complaints; saying “just deal with it”; not investigating whether child needs more challenge | Allowing child to stay home (reinforces avoidance); minimizing fears (“You’ll be fine”); forcing sudden return without gradual exposure | Not taking reports seriously; telling child to “stand up for yourself”; handling it yourself without school involvement | Assuming child is lazy; increasing pressure; comparison to siblings; not requesting assessment | Adding more activities; focusing only on grades; not recognizing emotional exhaustion as legitimate; expecting them to “push through” |

| What Helps | Enrichment; differentiated instruction; deeper projects; acceleration in specific subjects; extracurricular challenges | Gradual exposure; cognitive behavioral therapy; validation of feelings; maintaining routine; collaboration with school counselor; possible medication | Immediate school notification; documentation; safety plan; supervision during vulnerable times; peer support groups; possible classroom change | Psychoeducational evaluation; Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 Plan; specialized instruction; tutoring; breaking tasks into smaller steps; celebrating effort | Reduced extracurriculars; increased sleep; scheduled downtime; therapy for perfectionism; emphasis on process over outcome; family stress reduction |

Important Note

These categories often overlap. A child with undiagnosed dyslexia may develop anxiety about reading aloud. A bored gifted student may become a target for bullying. Multiple factors can coexist, which is why a comprehensive assessment is often necessary.

Age-by-Age Guidance

How you respond to “I hate school” should be tailored to your child’s developmental stage. Here’s what school refusal typically means at different ages and how to address it.

Ages 3–5 Preschool and Kindergarten

What “I Hate School” Usually Means

At this age, school refusal is most commonly driven by separation anxiety. The child isn’t necessarily unhappy at school; they’re anxious about being apart from their primary caregiver.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, separation anxiety is developmentally normal through age 3 and can persist in some children through kindergarten, especially if they haven’t had much practice with separations.3

Is Your Child’s Behavior Age-Typical?

Sometimes kids say “I hate school” because they’re pushing against normal developmental challenges. This guide helps you understand age-appropriate expectations.

→ Check Child Development Milestones by AgeWhat’s Normal vs. Concerning

Normal: Tears during drop-off that resolve within 5–10 minutes; clinginess in the morning; asking when you’ll return; initial resistance that improves over 2–4 weeks.

Concerning: Crying that continues for more than 15 minutes after you leave; child vomiting or having panic symptoms; complete inability to engage in activities; regression in toileting or sleep; no improvement after 4–6 weeks.

Parent Scripts for Ages 3–5

Morning Drop-Off Script

“I can see you’re feeling worried about me leaving. It’s okay to feel sad when we say goodbye. I’ll be back right after playground time [be specific]. Ms. Sarah will help you feel better. I love you, and I’ll see you soon.”

Then leave confidently, even if they’re crying. Trust the teacher.

“Don’t cry, you’re a big kid now”; “If you don’t stop crying, I’ll be late for work”; “Look, all the other kids are fine”; Sneaking out without saying goodbye; Lingering or repeatedly coming back

Immediate Actions for Ages 3–5

- Create a consistent goodbye routine (hug, kiss, specific phrase, then leave)

- Provide a transitional object (small family photo, special bracelet)

- Practice short separations in other settings (playdate at friend’s house)

- Ask teacher to have a special welcoming job ready when child arrives

- Keep goodbyes brief (under 2 minutes)

- Never sneak away — this increases anxiety

Ages 6–9 Early Elementary

What “I Hate School” Usually Means

This age group experiences school refusal primarily due to:

- Social anxiety (56% of school refusers in this age group have a primary anxiety disorder)4

- Academic pressure (standardized testing begins, reading fluency expectations increase)

- Peer relationship challenges (beginning awareness of social hierarchies)

- Undiagnosed learning differences becoming more apparent as academic demands increase

What’s Normal vs. Concerning

Normal: Occasional reluctance on Monday mornings or after breaks; complaints about specific assignments being boring or hard; temporary friend conflicts; adjustment challenges at the beginning of the school year.

Concerning: Regular physical complaints only on school mornings (headaches, stomachaches); crying or panic attacks before school; talking about not having friends; significant drop in grades; school counselor reporting social withdrawal; child asking to stay home multiple times per week.

Parent Scripts for Ages 6–9

Opening the Conversation

“I’ve noticed you’ve been saying you don’t want to go to school. I want to understand what’s happening. What’s the hardest part of your day at school?”

Follow-up questions: “When do you feel the worst — morning, lunch, a certain class?”; “Is there someone at school you wish you could talk to?”; “If you could change one thing about school, what would it be?”

“You’re being ridiculous, school is fine”; “I had to go to school and so do you”; “Your friends all go to school”; “There’s nothing wrong with you”; Comparing them to siblings

Immediate Actions for Ages 6–9

- Ask teacher for observation report (social interactions, academic engagement, anxiety signs)

- Create a “worry ladder” — list fears from smallest to biggest, tackle smallest first

- Establish a school check-in system (child can visit counselor or nurse when overwhelmed)

- Role-play challenging situations at home (asking to join a game, asking teacher for help)

- If academic struggles suspected, request psychoeducational evaluation through school

- Maintain school attendance while investigating — avoidance makes anxiety worse

Ages 10–12 Upper Elementary and Middle School

What “I Hate School” Usually Means

This is the peak age for school refusal behavior. Research shows 10–13-year-olds experience the highest rates of school avoidance.1 Key drivers include:

- Social anxiety and peer pressure intensifying

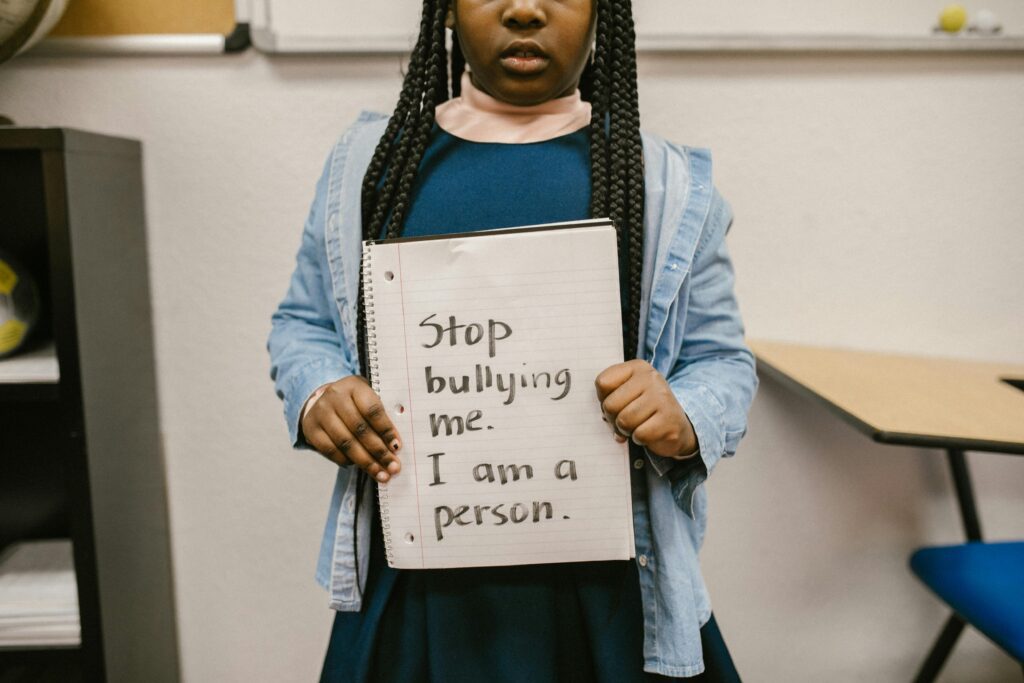

- Bullying (including cyberbullying)

- Academic pressure ramping up significantly

- Onset of depression or anxiety disorders

- Perfectionism and fear of failure

- Early signs of burnout

The transition to middle school is particularly vulnerable due to multiple teachers, changing classes, increased independence expectations, and heightened social complexity.

What’s Normal vs. Concerning

Normal: Complaints about workload; stress about grades; navigating friend drama; feeling self-conscious; wanting more independence from parents; occasional “mental health day” requests.

Concerning: Persistent talk of being worthless or a failure; social isolation; dramatic drop in grades; signs of being targeted (damaged belongings, reluctance to use phone/social media); substance experimentation; self-harm mentions; regular absence attempts.

Parent Scripts for Ages 10–12

Conversation Script for This Age

“I’ve noticed things seem really tough with school right now. I’m not going to force you to tell me everything, but I do need to understand enough to help. Can we talk about what’s making school feel so hard?”

If they’re reluctant: “You don’t have to tell me details, but can you tell me if this is about: friendships, schoolwork, feeling overwhelmed, or something else?”

If they mention social issues: “That sounds really painful. Are you feeling left out, or is someone being deliberately mean? There’s a difference, and it helps me know how to support you.”

“Middle school is hard for everyone, you just have to deal with it”; “When I was your age…”; “You’re being too sensitive”; “Just ignore the bullies”; “Can’t you just try harder?”

Immediate Actions for Ages 10–12

- Request meeting with school counselor and all relevant teachers

- Monitor social media and phone for cyberbullying (with transparency — tell them you’re doing this and why)

- Consider mental health screening if symptoms persist beyond 2 weeks

- Implement graduated return-to-school plan if avoidance has become severe

- Evaluate extracurricular load — may need to reduce activities temporarily

- Focus on effort and process, not grades, in your feedback at home

Ages 13–18 High School

What “I Hate School” Usually Means

Adolescent school refusal is typically more complex and can have serious consequences if not addressed. Common underlying issues:

- Clinical depression or anxiety disorders

- Chronic stress and burnout from academic and extracurricular pressure

- Social anxiety about fitting in, relationships, body image

- Bullying or social exclusion

- Substance use (school avoidance can be an early warning sign)

- Family stress (financial worries, parental conflict, caregiving responsibilities)

High schoolers are expected to be more independent and there is less structure than in earlier grades, making it more difficult for teachers and parents to intervene early.5

What’s Normal vs. Concerning

Normal: Stress about college applications; complaints about workload; senioritis; preference to stay home occasionally; friendship shifts; identity exploration; wanting more autonomy.

Concerning: Multiple days of absence without clear physical illness; failing grades when previously competent; withdrawal from all social activities; expressing hopelessness; mentions of self-harm or suicidal thoughts; dramatic personality changes; risk-taking behavior; evidence of substance use.

Parent Scripts for Ages 13–18

Conversation Script for Teens

“I know you’re struggling with school, and I want you to know I’m taking this seriously. I’m not going to lecture you or tell you to ‘just push through.’ But I am worried, and I need your help figuring out what’s going on so we can actually make this better. What would help right now?”

If they’re defensive: “I get that you might not want to talk to me about this. Would you rather talk to someone else — a counselor, another family member, a therapist? I just need to know you’re getting support somewhere.”

“You’re going to ruin your future”; “You’re throwing away your opportunities”; “Do you know how much we sacrifice for you?”; “You’re being lazy”; “What’s wrong with you?”

Immediate Actions for Ages 13–18

- Arrange mental health evaluation (primary care doctor can refer)

- Consider whether academic expectations are realistic for this particular teen

- Meet with school counselor to discuss support options (reduced course load, therapy during school hours, etc.)

- Rule out physical health issues (thyroid, anemia, sleep disorders, chronic illness)

- Explore alternative education options if traditional school is genuinely not working (online school, alternative programs, etc.)

- If safety concerns exist, remove means of self-harm and get immediate professional help

Build a Balanced Home That Supports Growth

Understanding school struggles is just one part. Discover practical strategies that support your child’s emotional and academic growth every day.

→ Start with 5 Real Parenting TipsExact Parent Scripts: What to Say and What Not to Say

The words you choose matter enormously when your child is in distress. Here are specific scripts for common scenarios.

When Your Child First Says “I Hate School”

“I hear you. It sounds like school feels really hard right now. Can you tell me more about that? What’s the toughest part?”

Why this works: You validate the feeling without agreeing with the conclusion, and you open space for them to share more specific information.

“No you don’t, you’re just tired”; “That’s not a choice, you have to go”; “Stop being dramatic”

Why this fails: Dismisses their experience, shuts down communication, and increases their distress without addressing the underlying issue.

When They Can’t Articulate What’s Wrong

“Sometimes feelings are hard to put into words. Let me ask some questions that might help:

- Is it about the work being too hard, too easy, or just right but too much of it?

- Is it about other kids — feeling left out, or someone being mean?

- Is it about a grown-up at school?

- Is it a worried feeling in your body, or more like you’re just not interested?

- Is there a specific time of day that feels worst?”

When You Suspect Anxiety

“I notice your stomach hurts a lot on school mornings but not on weekends. I’m wondering if your body is trying to tell you that you’re feeling worried about something at school. Worry can make our bodies feel sick even when we’re not actually sick. Does that sound like what might be happening?”

“Worry is like a very bossy alarm system. It thinks it’s protecting you, but sometimes it goes off when you’re actually safe. We can teach your worry to calm down.”

“There’s nothing to be anxious about”; “You’re fine, you just need to relax”; “Just don’t think about it”

Follow-Up Questions That Help

- “When you imagine going to school tomorrow, what’s the first thing that makes you feel bad?”

- “If you could skip one part of the school day, which part would it be?”

- “Who at school makes you feel safest?”

- “What would need to change for school to feel even a little bit better?”

- “On a scale of 1-10, how bad does school feel? What would make it move to a 7 instead of a 9?”

Teacher Conversation Scripts

Email Template to Teacher

Subject: Requesting support for [Child’s Name] — School refusal concerns

Dear [Teacher’s Name],

I’m reaching out because [Child’s Name] has been expressing significant distress about coming to school. Over the past [timeframe], they have [specific observations: complained of stomachaches on school mornings, cried before school, asked to stay home X times].

When I ask what’s troubling them, they say [child’s words]. I want to understand what you’re observing at school so we can work together to support them.

Could you share:

- How [Child] seems during class (engaged, withdrawn, anxious)?

- Whether you’ve noticed any social challenges?

- Whether they’re keeping up academically?

- Any times of day when they seem most/least comfortable?

I’d appreciate scheduling a brief call or meeting to discuss how we can best support [Child] at home and school. Thank you for your partnership.

Warm regards,

[Your Name]

In-Person Meeting Script

“Thank you for meeting with me. I’m concerned about [Child] and want to make sure we’re on the same page. Here’s what I’m seeing at home: [specific behaviors]. What are you seeing at school?”

After teacher shares observations:

“That’s really helpful. Based on what we both see, I think we need a plan that includes [your proposed actions]. Can we also [specific school-based support you’re requesting]? What do you think would help from your perspective?”

“How should we check in with each other? Can we touch base weekly for the next month to see if things are improving?”

Step-by-Step Action Plan

Your Roadmap to Addressing School Refusal

First 24 Hours: Gather Information

Your goals: Stay calm, validate your child’s feelings, and start collecting data.

- Have an initial calm conversation using scripts from this guide

- Observe physical symptoms: When do they appear? Do they resolve when school is not imminent?

- Note specific statements your child makes (write them down exactly)

- Review recent communications from school (emails, newsletters, grade reports)

- Check in with your child about specific parts of the day (morning, lunch, certain classes, bus)

- Assess whether this is new or escalating behavior

- Maintain school attendance if possible while you investigate

Important: Resist the urge to keep them home unless there are genuine safety concerns (credible bullying threat, severe panic symptoms). Early avoidance creates a pattern that’s harder to break.

First Week: Identify Patterns and Reach Out to School

Your goals: Determine whether this is anxiety, boredom, social issues, learning challenges, or burnout. Begin collaboration with school.

Observation Checklist

- Physical symptoms only on school days? (Suggests anxiety)

- Complaints about work being too easy or pointless? (Suggests boredom)

- References to specific kids, lunch, or recess being problematic? (Suggests social issues/bullying)

- Avoidance of homework, frustration with reading/math, statements about being “dumb”? (Suggests learning difficulty)

- Chronic fatigue, emotional flatness, perfectionism, physical exhaustion? (Suggests burnout)

School Communication Steps

- Email teacher using template from this guide

- If bullying suspected, also email school counselor and principal

- Request observation report from teacher

- Ask to schedule meeting within one week

- Document all communications (keep a file)

Home Support Strategies

- Maintain routines (bedtime, morning routine, screen time limits)

- Ensure adequate sleep (age-appropriate amounts)

- Create daily check-in time (10-15 minutes) to talk about school

- Avoid morning battles — get child to school even if late

- Plan something small and positive after school (snack together, 20 min game time)

- Reduce non-essential commitments temporarily

First Month: Implement Targeted Interventions

Your goals: Based on your identified cause, implement specific strategies and monitor effectiveness.

If Anxiety is the Issue:

- Create “worry ladder” — gradual exposure starting with least anxiety-provoking situations

- Teach simple anxiety management: deep breathing (4 counts in, 4 hold, 6 out), grounding techniques

- Arrange for child to check in with school counselor upon arrival

- Consider referral to therapist specializing in CBT for anxiety

- Read about anxiety together (age-appropriate books)

- Never force sudden return after extended absence; use graduated reintegration

If Boredom is the Issue:

- Request academic assessment to confirm child is working below potential

- Explore enrichment options (gifted program, differentiated instruction, grade acceleration in specific subjects)

- Provide challenging activities at home that engage their interests

- Help them find meaning in current work (how it connects to bigger goals)

- Advocate for more complex projects rather than “more of the same” work

If Bullying is the Issue:

- Formal documentation to school with specific incidents, dates, witnesses

- Request safety plan (supervision during vulnerable times, designated safe person to report to)

- Daily check-ins with school counselor or trusted adult

- Possible schedule adjustment (different lunch period, classroom change)

- Help child develop scripts for responding to bullies

- Build external social connections (activities outside school)

- Consider peer support group or social skills coaching

If Learning Difficulty is the Issue:

- Request formal psychoeducational evaluation through school (submit written request)

- Private evaluation if school delays (educational psychologist or neuropsychologist)

- If disability identified, develop IEP or 504 Plan

- Specialized tutoring in area of weakness

- Emphasize effort and specific strategies rather than outcomes

- Help child understand their learning profile (not “dumb,” brain works differently)

- Advocate for appropriate accommodations (extended time, smaller chunks, etc.)

If Burnout is the Issue:

- Audit all commitments — cut non-essential activities

- Prioritize sleep (absolutely non-negotiable)

- Build in weekly downtime with no productivity pressure

- Address perfectionism through therapy or parent coaching

- Shift family culture from achievement-focused to process-focused

- Model healthy boundaries and self-care

- Consider temporary reduction in course rigor (with school counselor support)

Ongoing: Monitor and Adjust

- Weekly check-in with child: “On a scale of 1-10, how is school feeling?”

- Biweekly email check-in with teacher

- Monthly review of whether interventions are working

- Celebrate small improvements (not just perfect attendance)

- Be prepared to adjust approach if initial plan isn’t working

- Don’t hesitate to seek professional help if home and school strategies aren’t enough

School Collaboration: Working with Teachers and Counselors

Effective partnership with your child’s school is essential. Here’s how to approach this collaboration professionally and productively.

Initial Email Template (Detailed Version)

Subject: Support Needed: [Child Name] – School Avoidance Concerns

Dear [Teacher/Counselor Name],

I hope this email finds you well. I’m writing to request your support and collaboration regarding [Child’s Name].

Current Situation:

Over the past [specific timeframe: two weeks, month], [Child] has shown increasing reluctance to attend school. Specifically, I’ve observed:

- [Specific behavior: crying each morning, complaining of stomachaches, asking to stay home]

- [Frequency: 3-4 times per week]

- [Child’s statements: “I hate school,” “Nobody likes me,” “It’s too hard,” etc.]

What I’m Seeing at Home:

[Describe: anxiety symptoms, social withdrawal, homework struggles, changes in mood, sleep issues, etc.]

What I Need from You:

- Your observations of [Child] in class: engagement level, peer interactions, academic performance, any concerning behaviors

- Whether you’ve noticed any incidents that might have triggered this (peer conflict, difficult assignment, changes in classroom dynamics)

- A meeting to develop a coordinated support plan

My Proposed Next Steps:

[Mention any actions you’re already taking: scheduling doctor appointment, increasing communication, implementing calming strategies at home]

I’m committed to working together to support [Child] and ensure they feel safe and successful at school. Could we schedule a time to talk this week?

Thank you for your partnership and expertise.

Warmly,

[Your Name]

[Contact Information]

Questions to Ask in School Meetings

- “What are you observing in terms of [child’s] engagement and mood in class?”

- “Have you noticed any peer relationship challenges?”

- “Is their academic work on grade level, or are there areas where they’re struggling?”

- “What time of day or which activities seem to be most difficult for them?”

- “Have there been any changes in classroom dynamics, teaching staff, or schedules recently?”

- “What supports are available through the school? (counselor check-ins, safe space access, etc.)”

- “How can we communicate regularly about how things are going?”

- “If things don’t improve with initial supports, what are the next steps?”

Simple Support Plan Template

Collaborative Support Plan

Student: [Name]

Date: [Date]

Team Members: Parent(s), Teacher(s), Counselor, [Other relevant staff]

Identified Concern:

[Brief description: School avoidance related to anxiety/social challenges/academic struggles/etc.]

Student Strengths:

[List: loves reading, good friend to others, creative, responsible, curious about science, etc.]

Specific Supports at School:

- [Example: Check in with counselor each morning upon arrival]

- [Example: Preferred seating away from distracting peers]

- [Example: Access to quiet space when overwhelmed]

- [Example: Teacher will privately check in mid-morning: “How are you doing?”]

- [Example: Modified homework assignments to reduce overwhelm]

Supports at Home:

- [Example: Consistent bedtime routine to ensure adequate sleep]

- [Example: Morning check-in using “worry scale” to identify anxiety level]

- [Example: Practice calming strategies before bed]

Communication Plan:

[Example: Teacher will email parent every Friday with update. Parent will email immediately if concerning morning occurs.]

Progress Monitoring:

We will reassess this plan in [timeframe: 3 weeks, 1 month] to determine effectiveness and make adjustments as needed.

When to Escalate:

If [specific red flags: absence increases, panic symptoms worsen, grades drop significantly, bullying is identified], we will [specific action: refer to school psychologist, request evaluation, involve administration].

Know Your Rights

If your child has a diagnosed condition (anxiety disorder, depression, ADHD, learning disability, etc.) that impacts their education, they may qualify for formal accommodations:

- 504 Plan: Provides accommodations for students with disabilities who don’t need specialized instruction (examples: extended time on tests, access to counselor, modified attendance policy during mental health crisis)

- IEP (Individualized Education Program): Provides specialized instruction and services for students with qualifying disabilities that impact learning

You can request an evaluation for either by submitting a written request to your school principal or special education coordinator. Schools are legally required to respond within specific timeframes (typically 30 days to decide whether to evaluate).

When to Seek Professional Help

While many cases of school refusal can be addressed with parent-school collaboration, some situations require professional mental health intervention.

⚠️ Seek Immediate Help If:

- Your child expresses thoughts of self-harm or suicide

- They exhibit self-harming behaviors (cutting, burning, hitting self)

- They show signs of severe depression (hopelessness, not eating, not sleeping, loss of interest in everything)

- There’s evidence of substance use

- They become physically aggressive when pushed to attend school

- You discover credible, serious bullying or abuse

Resources: Call 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) or go to your nearest emergency room.

Consider Professional Evaluation If:

- School refusal persists for more than 2-3 weeks despite home and school interventions

- Physical symptoms are severe (panic attacks, vomiting, severe headaches)

- Your child has missed more than a week of school due to emotional reasons

- There’s a pattern of increasing avoidance over several months

- Family functioning is significantly impacted (constant conflict, parental stress affecting work, sibling resentment)

- You suspect an undiagnosed anxiety disorder, depression, or ADHD

- Learning difficulties are suspected but school hasn’t completed evaluation

- Your own anxiety about the situation is overwhelming (parent therapy can help too)

Who to Consult

Primary Care Pediatrician

Good for: Initial assessment, ruling out medical causes (thyroid issues, anemia, chronic illness), mental health screening, medication referrals if needed, connecting you to specialists

Ask for: Complete physical exam, mental health screening (standardized questionnaires for anxiety/depression), referrals to therapists in your area

Licensed Therapist (Psychologist, LCSW, LPC)

Good for: Individual therapy addressing anxiety, depression, social skills, trauma; parent coaching on behavioral strategies

Look for: Specialization in child/adolescent therapy, experience with school refusal specifically, training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Evidence base: CBT has been shown to increase school attendance by 40-60% in students with anxiety-driven school refusal.6

School Psychologist

Good for: Psychoeducational evaluation (identifying learning disabilities, cognitive strengths/weaknesses, attention issues), consulting on behavioral plans at school

Ask for: Comprehensive evaluation if learning difficulties or ADHD suspected; consultation on accommodations

Educational Psychologist or Neuropsychologist (Private)

Good for: Comprehensive assessment when school evaluation is inadequate or delayed, complex cases involving multiple issues, detailed recommendations for learning accommodations

Note: Can be expensive ($2,000-$5,000) but provides detailed roadmap

Child Psychiatrist

Good for: Medication evaluation and management when anxiety or depression is severe, cases not responding to therapy alone

Common medications: SSRIs for anxiety/depression (after therapy has been attempted); sometimes medications for ADHD or sleep issues if those are contributing factors

Evidence-Based Interventions That Work

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Gold standard treatment for anxiety-driven school refusal. Focuses on identifying anxious thoughts, challenging them with evidence, and gradual exposure to feared situations.

Typical duration: 12-16 sessions

Effectiveness: 60-70% of children with school refusal show significant improvement2

Exposure Therapy (Component of CBT)

Systematic, gradual exposure to school environment starting with least-threatening situations (e.g., visiting school on weekend, attending for one period, full day with supports).

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

Helpful for teens with more intense emotional responses, includes mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation skills.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

For younger children (ages 2-7) with separation anxiety contributing to school refusal; strengthens attachment while building child’s independence.

Family Therapy

When family dynamics (parental anxiety, marital conflict, overprotection) are contributing to or maintaining school refusal.

Graduated Return-to-School Protocol

If your child has been absent from school for an extended period, a gradual return plan is essential:

- Week 1: Visit school after hours to walk around, see classroom

- Week 2: Attend for 1-2 hours during least stressful part of day (usually morning)

- Week 3: Attend half day

- Week 4: Full day with option to check in with counselor

- Week 5: Full day, regular schedule with supports faded gradually

Important: Steps move forward only, never backward. Child stays at current step until comfortable, then advances. Missing one day doesn’t mean starting over.

Real-Life Case Studies

These composite case studies (drawn from common patterns in clinical practice) illustrate how different underlying causes present and respond to intervention.

Case Study 1: Emma, Age 7 — Boredom Masquerading as Misbehavior

The Problem:Emma’s teacher reported that she was “disruptive” — calling out answers, finishing work in minutes then wandering around the classroom, asking to go to the bathroom multiple times per class. At home, Emma said school was “boring” and “for babies.” Her parents initially dismissed this, thinking she was just avoiding work.

The Investigation:Emma’s mother requested to observe a reading lesson. She noticed Emma reading three grade levels above her peers. When given a complex logic puzzle at home, Emma worked on it intensely for an hour. The school psychologist conducted testing that revealed Emma was reading at a 5th-grade level in 2nd grade and had exceptional reasoning abilities.

The Intervention:- Teacher provided differentiated reading materials at Emma’s level

- Emma joined 4th-grade class for reading block

- When she finished work early, she had “challenge folder” with enrichment activities instead of “more of the same”

- Parents enrolled her in weekend STEM program for social connection with intellectual peers

Within three weeks, disruptive behavior decreased by 90%. Emma started saying she “liked school again.” Her teacher noted she was more engaged and seemed happier. The key was recognizing that her behavior was a symptom of unmet intellectual needs, not defiance.

Case Study 2: Marcus, Age 11 — Anxiety and Perfectionism

The Problem:Marcus, a straight-A student, began having stomachaches every school morning. He would vomit before tests. He asked to stay home 2-3 times per week. When home, he seemed fine within an hour. His parents thought he was faking. The pediatrician found no physical cause.

The Investigation:Marcus’s mother used the conversation scripts from this guide. Marcus eventually shared that he was “afraid of failing” and that “if I don’t get perfect scores, I won’t get into college.” He was staying up until midnight redoing homework to make it “perfect.” The school counselor reported Marcus had cried in her office after getting an A- on a project.

The Intervention:- Family meeting where parents explicitly gave permission to be “imperfect” and shared their own failures

- 12 sessions of CBT focusing on cognitive distortions (“If I get one B, my future is ruined”)

- Exposure hierarchy: deliberately leaving one homework problem incomplete, turning in “good enough” work without checking it five times

- Parents stopped asking “How did you do?” and started asking “What did you learn today?”

- School counselor check-ins before tests to practice calming strategies

After two months, morning vomiting stopped. Marcus still experienced some test anxiety but had tools to manage it. His parents noticed he seemed “lighter” and more willing to try new things. Most importantly, he attended school consistently and his stomachaches became rare rather than daily.

Case Study 3: Jasmine, Age 14 — Undiagnosed Learning Disability

The Problem:Jasmine said she “hated school” and was “stupid.” Her grades had dropped from Bs to Ds over two years. She refused to do homework, saying “What’s the point? I’m going to fail anyway.” Teachers described her as “not trying” and “capable but lazy.”

The Investigation:Jasmine’s father noticed she avoided reading aloud and took significantly longer than her siblings to complete homework. He requested a psychoeducational evaluation. Testing revealed dyslexia and a working memory weakness that had been compensated for in elementary school but became overwhelming as text complexity increased.

The Intervention:- IEP with specialized reading instruction using Orton-Gillingham method

- Accommodations: extended time on tests, ability to use text-to-speech software, reduced reading load

- Specialized tutor twice weekly focusing on decoding skills

- Therapy to address self-esteem damage from years of feeling “dumb”

- Parents educated themselves about dyslexia and helped Jasmine understand her brain differences

Progress was gradual. After six months, Jasmine’s reading fluency improved by one grade level. More importantly, she stopped calling herself stupid. She began using her accommodations without shame. A year later, her grades were back to Bs and Cs, and she was applying to colleges with strong support programs for students with learning disabilities. She no longer refused to go to school.

Frequently Asked Questions

Occasional planned mental health days (no more than once per quarter) can be beneficial if used strategically — for genuine overwhelm recovery, not avoidance. However, regularly allowing your child to stay home when they express distress actually worsens anxiety. Avoidance strengthens fear. Instead, validate the feeling while maintaining attendance, then address the root cause. Exception: If there’s a credible safety concern or severe panic symptoms, short-term absence with a graduated return plan may be necessary.

Physical symptoms without medical cause often indicate anxiety or stress. The symptoms are real — anxiety genuinely causes stomachaches, headaches, nausea, and fatigue. Help your child understand the mind-body connection: “Your body is sending worry signals.” Address the underlying anxiety rather than debating whether they’re “really” sick. A mental health professional can help with this distinction and teach coping strategies.

Occasional reluctance (“Ugh, do I have to go to school today?”) is normal. It becomes serious when: it happens more than once weekly, physical symptoms are involved, it’s accompanied by other behavioral changes (sleep issues, mood changes, social withdrawal), academic performance declines, or it persists despite your supportive efforts for more than 2-3 weeks. Trust your parental instinct — if it feels different or concerning, it probably warrants investigation.

Sometimes brief episodes resolve naturally (adjustment to new school year, temporary friend conflict). However, persistent school refusal rarely improves without intervention. Research shows that untreated school refusal can lead to chronic absenteeism, increased mental health problems in adulthood, and social and economic difficulties later in life. Early intervention produces the best outcomes. The longer avoidance continues, the harder it becomes to break the pattern.

Homeschooling can be appropriate for some children (those who are genuinely better suited to self-paced learning, have specific educational needs, or face unresolvable school environment issues). However, switching to homeschooling specifically to avoid addressing anxiety, social skills challenges, or other underlying issues usually doesn’t solve the problem — it postpones dealing with it. If considering homeschooling, first rule out and address anxiety, learning disabilities, and bullying. Consult a mental health professional about whether this is the right choice for your specific situation.

Try different communication methods: drawing their feelings, writing a note, having conversations while doing side-by-side activities (walking, driving, playing catch), using hypothetical scenarios (“If a kid felt worried at school, what do you think they’d be worried about?”). Give them options to talk to someone else (school counselor, therapist, trusted family member). Sometimes children find it easier to open up to professionals than parents. Also observe behavior patterns rather than relying only on verbal communication — what times, situations, or subjects trigger the most distress?

In most cases, yes — maintain school attendance while you investigate and address the root cause. Staying calm and matter-of-fact (“I know this is hard, and we’re going to figure out why, but today you’re going to school”) is more effective than either forcing angrily or giving in. Getting them there, even if late, even if upset, prevents the avoidance cycle. However, if they’re experiencing severe panic (hyperventilating, vomiting, dissociating) or there’s a credible safety threat, seek immediate professional guidance about a graduated return plan.

Document everything in writing. Send emails rather than relying on verbal conversations. Request a formal meeting with teacher, counselor, and administrator. Use phrases like “I’m requesting support under Section 504” (if applicable) or “I’m formally requesting an evaluation.” If the school continues to be unresponsive, contact your district’s special education department or consider consulting an education advocate. You can also file a complaint with your state’s Department of Education if legal rights are being violated.

When school refusal is driven by diagnosed anxiety or depression that hasn’t responded adequately to therapy alone, medication can be a helpful part of a comprehensive treatment plan. SSRIs (like sertraline or fluoxetine) are most commonly prescribed for pediatric anxiety. Medication is not typically a first-line treatment but can enable a child to engage in exposure therapy when anxiety is too severe otherwise. Always work with a child psychiatrist and combine medication with therapy for best outcomes. Medication alone, without addressing underlying issues, is rarely effective.

This varies significantly based on underlying cause, severity, how long it’s been going on, and intervention effectiveness. Mild cases addressed early may improve within 3-6 weeks. More entrenched patterns or complex issues (multiple underlying causes, extended absences) may take 3-6 months or longer. The key is consistent intervention and patience. Progress often isn’t linear — there will be better weeks and harder weeks. The goal is overall trend toward improvement, not perfection.

Extended absences require a structured return plan. Work with the school on a graduated reintegration schedule (see Professional Help section of this guide). Start with brief visits during non-stressful times, gradually increasing to full days. Be prepared for this to take several weeks. The school may offer homebound instruction during the transition. Important: Don’t wait until the problem is “completely solved” before returning — partial return helps recovery. The longer the absence, the more anxiety builds about returning.

Yes, particularly for adolescents. Excessive social media use is correlated with increased anxiety, depression, and sleep deprivation — all of which contribute to school avoidance. Cyberbullying extends school social stress into home time. Late-night screen use disrupts sleep, making morning wake-ups more difficult. Gaming or social media also provides an reinforcing alternative to school. Consider a screen time audit: track daily use, establish boundaries (no phones in bedrooms overnight, no social media on school mornings), and ensure at least one hour of screen-free time before bed.

No. This is a cognitive distortion common in anxious children and teens. They compare their internal experience (awareness of their own struggle) to others’ external appearance (who often hide their difficulties). Help them understand that many students struggle privately. Share age-appropriate statistics: about 32% of adolescents experience anxiety disorders, learning differences affect 15-20% of the population, and most students experience significant stress at some point. Normalize struggle as part of learning rather than evidence of inadequacy.

A significant one. Children are highly attuned to parental anxiety. If you’re anxious about their distress, communicate uncertainty about whether they should go, or become visibly upset during drop-offs, you inadvertently reinforce their perception that school is dangerous. Work on managing your own anxiety — possibly through therapy — so you can respond to your child with calm confidence. Model distress tolerance: “This is hard, but we can handle hard things.” Your calm conviction that they’re safe and capable helps them believe it too.

Yes, in age-appropriate ways. Siblings notice when one child is getting extra attention or being “allowed” to stay home. Brief explanation prevents resentment and confusion: “Your brother/sister is having a hard time with worry feelings, and we’re working with their doctor to help them feel better.” Emphasize that each family member gets help with what they need. Protect details that would violate privacy, but loop siblings in enough that they understand and can be supportive rather than jealous or worried.

Printable Takeaway Resources

Quick Parent Scripts — Print & Keep

When They Say “I Hate School”:

“I hear you. It sounds like school feels really hard right now. Can you tell me more about that? What’s the toughest part?”

When You See Morning Anxiety:

“I notice your stomach hurts on school mornings. I’m wondering if your body is trying to tell you that you’re feeling worried about something. Worry can make our bodies feel sick even when we’re not actually sick. Does that sound like what might be happening?”

When They Can’t Explain:

“Sometimes feelings are hard to put into words. Is it about the work being too hard, too easy, or just too much? Is it about other kids? Is it a worried feeling, or more like you’re just not interested?”

Drop-Off Script:

“I know this is hard. We’re figuring it out together. Right now, today, you’re going to school. I love you and I’ll see you at [specific time].”

What NOT to Say:

“You’re fine” • “There’s nothing to worry about” • “Just try harder” • “Everyone else is fine” • “Stop being dramatic”

Decision Checklist — What’s Really Going On?

Check all that apply:

- Physical symptoms (stomachache, headache) only on school days

- Relief/symptom disappearance when allowed to stay home

- Crying, clinging, panic before school

- Mentions of specific fears (“What if I throw up?”)

- → Likely: Anxiety

- Says work is “too easy” or “boring”

- Finishes assignments much faster than peers

- No physical symptoms, just disengagement

- Misbehavior in class due to finishing early

- → Likely: Boredom/Need for Challenge

- Fear of specific times (lunch, recess, bus)

- Mentions “mean kids” or “no friends”

- Missing belongings or physical injuries

- Reluctance to use phone or social media

- → Likely: Bullying/Social Issues

- Says “I’m stupid” or “I can’t do it”

- Avoids homework, especially reading/math

- Takes much longer than peers on assignments

- Declining grades despite effort

- → Likely: Learning Difficulty

- Chronic fatigue despite adequate sleep

- Loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities

- Perfectionism and fear of failure

- Irritability and emotional flatness

- → Likely: Burnout

7-Day Action Starter Plan

Day 1: Have calm conversation using parent scripts. Document what child says (exact words).

Day 2: Observe and track: When do symptoms appear? What makes them better/worse? Note patterns.

Day 3: Email teacher using template from guide. Request their observations.

Day 4: Review teacher response. Ask child follow-up questions based on what you’ve learned.

Day 5: Use decision checklist to identify most likely cause. Research appropriate interventions.

Day 6: Implement one home strategy (e.g., if anxiety: practice calming breathing; if boredom: provide challenging activity; if burnout: reduce one extracurricular).

Day 7: Request school meeting if not already scheduled. Prepare what you want to communicate and ask.

Week 2 onward: Continue interventions. Monitor daily on 1-10 scale. Reassess every two weeks. Seek professional help if no improvement by week 3-4.

References and Research

- Medical Xpress. (2025). “Survey reveals top reasons why kids avoid going to school.” Study based on data from National Institutes of Health research on school avoidance prevalence.

- Egger, H. L., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2003). “School Refusal and Psychiatric Disorders: A Community Study.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(7), 797–807. Research indicates school refusal is associated with anxiety disorders, depression, ODD, PTSD, and adjustment disorders.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2024). “Separation Anxiety and School Refusal.” AAP clinical guidance on normal developmental separation anxiety through age 3 and persistence in some children through kindergarten.

- Nevada Mental Health. (2024). “When Your Child Says No to School: Tips for Handling School Refusal.” Dr. Sid Khurana notes that approximately 56% of elementary-age children with school refusal have a primary anxiety disorder.

- Meridian Psychiatric Partners. (2025). “How to help a child who’s struggling with school refusal.” Sarah Biehl, LCPC, discusses challenges specific to high school students including increased independence expectations and reduced structure.

- Maynard, B. R., et al. (2015). “Treatment for School Refusal Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Campbell Systematic Reviews. Research demonstrates CBT increases school attendance by 40–60% in students with anxiety-driven school refusal.

- Di Vincenzo, C., et al. (2024). “School refusal behavior in children and adolescents.” PMC – National Center for Biotechnology Information. Comprehensive review of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric factors in school refusal.

- Zaky, E. A. (2020). “School Refusal and Psychiatric Disorders in Children: Prevalence and Risk Factors.” Egyptian Journal of Health Care. Study shows school refusal due to anxiety affects approximately 2% of school-aged children and accounts for 5% of pediatric mental health referrals.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). “Children’s Mental Health: Anxiety and Depression.” Data indicates approximately 9.4% of children aged 3–17 years have been diagnosed with anxiety disorders.

- Bright Path Behavioral Health. (2025). “School Anxiety and Refusal: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment.” Research compilation from National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) indicating 32% of adolescents experience some form of anxiety disorder.

- Kawsar, M. D. S., et al. (2022). “School Refusal.” StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. Overview of school refusal as a symptom of social anxiety disorder, GAD, specific phobias, major depression, ODD, and PTSD.

- Child Mind Institute. (2024). “School Refusal and Anxiety: What Parents Need to Know.” Clinical guidance on evidence-based interventions for school avoidance driven by anxiety and emotional distress.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). “Adolescent Mental Health.” Global data on prevalence of anxiety, depression, and school-related mental health challenges in children and adolescents worldwide.

This article synthesizes peer-reviewed research, clinical guidelines from major health organizations, and evidence-based practices in child psychology and pediatric medicine. All recommendations align with current standards from the American Academy of Pediatrics, CDC, NIMH, and leading research institutions. Parents should consult with qualified healthcare and mental health professionals for individual guidance specific to their child’s situation.